UK Dub: Smashing The Palace

“I call dub the music of chance because you cut something out and you unearth a jewel which you didn’t hear before. It’s kind of the opposite of what Brian Wilson or Phil Spector would do. It’s smashing the palace and then finding something in the rubble” — Mark Stewart, “DUB is A Life Philosophy”, 2022

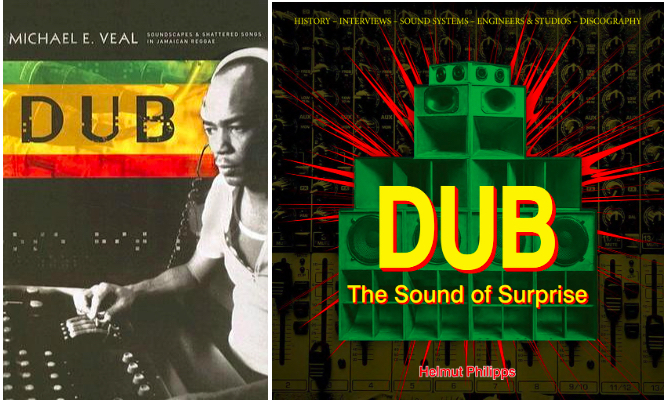

Because of its undeniably subversive potential, dub has captured the minds of academics keen to provide complex insights into the cultural disruptions created by dub since its inception in the dancehalls of Kingston. Author Michael Veal provided doctoral level dissections of dub songs and dub as a cultural force in his 2007 book, Dub: Soundscapes and Shattered Sounds in Jamaican Reggae. The level of analysis was astounding with Veal micro analysing the constituent elements of some classic dubs as well as writing a complex dub coda that plays on the idea of dub’s incursion into electronic music as a set of portable sonic strategies.

Helmut Philipp’s Dub: The Sound of Surprise offers a more grounded view of dub, framing it as routine studio practice in Jamaica. For Philipp, dub is strictly defined as one-off analog improvisation tied to original Jamaican reggae recordings. He dismisses broader interpretations as misguided, only reluctantly acknowledging offshoots like neo-dub and eurodub. In his words, “Jamaica has allowed dub to be taken out of its hands and is leaving the counteraction to other countries.”

It’s clear that there is no middle ground to take here and indeed if we boil down the essence of the schism between Veal and Phillips it amounts to Philipps’ notion of dub as a noun and Veal’s treatment of dub as a verb. Dub’s second life in the UK seems to be a perfect case of the studio strategies of Jamaican engineers coming across the Atlantic and having a life of their own, with dub the noun being displaced by the momentum of dub as a verb.

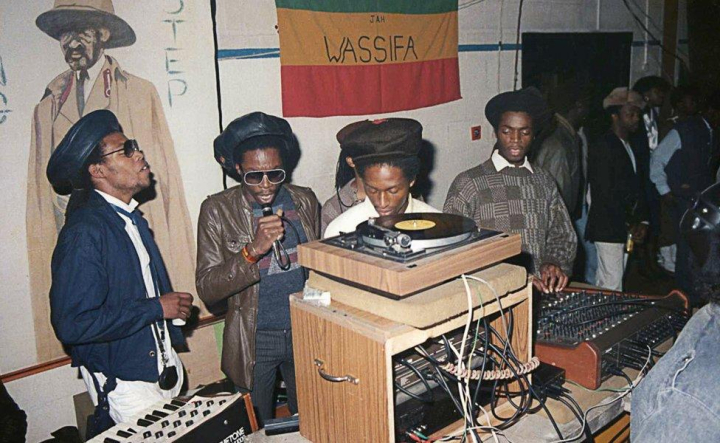

In the 1950s and ’60s, waves of Jamaican immigration brought sound system culture to London, which rapidly spread across some key UK cities. By the early ’70s, hundreds of systems catered to the children of these immigrants. Dub, born in Kingston’s dancehalls through experimentation, crossed the Atlantic and took on an almost undefinable heaviness when amplified through the powerful UK sound systems—and for a while were a no-go for white audiences.

By the mid-1970s, sound system pioneer Lloydie Coxsone released one of the UK’s first dub albums, King of the Dub Rock (1975), under Sir Coxsone Sound. Though partly mixed in the UK, much of it was produced by Gussie Clark in Jamaica with rhythms from King Tubby’s studio—making it not purely UK dub. Still, it captured the sound that Coxsone and his crew played at their Roaring Twenties residency in London, reflecting the growing appetite for dub in the UK scene.

Bob Marley’s mainstream success opened doors for British reggae bands like Matumbi, Aswad, and Steel Pulse, who secured major label deals in the mid-’70s. With album contracts came room for dub experimentation. Among the most innovative was Dennis Bovell—a multi-instrumentalist whose work as Blackbeard produced some of the UK’s earliest full dub albums. His stripped-down reworks of earlier tracks closely aligned with traditional dub’s definition: one-off analog reinterpretations of pre-recorded material.

Around the same time Bovell was pioneering dub, a young Adrian Sherwood entered the scene. Though only in his early 20s, Sherwood had spent years immersed in Jamaican music. Rather than replicate traditional dub, he used his On-U Sound label to push boundaries—blending abrasive textures, eclectic samples, and cross-genre collaborations. His work transformed dub into a platform for the remixing strategies to exist beyond reggae.

UK Dub’s history is full of unlikely encounters that led to remarkable outcomes. Sound systems thrived on surprising crowds with exclusive dubplates—some of which came not from Jamaican expats, but from unexpected sources like John Hassell, a nearly blind white pensioner in suburban Richmond. As Dennis Bovell recounts in Reggae Britannia, Hassell’s studio at 21 Nassau Road, Barnes, became a key site for high-quality dubplate cutting. Another surprising figure is John Collins, a white reggae enthusiast from Tottenham. Despite not being of Caribbean descent, Collins became a pioneering UK dub producer. His deep connection to multicultural London shaped his work, including producing The Specials’ “Ghost Town” and founding Local Records—proof of his authentic grasp of dub’s sonic and cultural roots.

In the post-punk era, “dub” evolved from a remixing technique into a creative philosophy. While reggae and punk had briefly intersected, dub and post-punk formed a deeper bond. Artists like The Pop Group, Public Image Ltd, and The Slits embraced dub’s echo, reverb, and bass-heavy minimalism to break from punk’s rawness. As Mark Stewart put it, dub became a way to “smash the palace”—a radical, deconstructive approach that reshaped post-punk’s sound into something darker, spacier, and more experimental.

Throughout the 1980s, UK sound systems like Jah Shaka, Saxon, and Unity kept dub’s communal spirit alive through regular countrywide dances. Inspired by the deep, hypnotic sound of Shaka sessions, a new wave of producers developed UK steppers—a futuristic, bass-heavy style driven by keyboards and home studio tech. This response to Jamaica’s shift toward digital dancehall saw artists like Iration Steppas, Alpha & Omega, and the Disciples reimagining dub for a new generation.My suggestion for those seeking a deep bath in steppers is to listen to Ossia’s excellent 2 hour show from 2021 dedicated to UK Dub and Steppers.

As electronic dance music surged in the UK during the 1980s, bleep techno emerged as the first truly British style to absorb dub both sonically and culturally. Rooted in Northern cities like Sheffield and Leeds, it fused Detroit techno’s minimalism with dub’s sub-bass and spatial aesthetics, laying the groundwork for jungle and dubstep.

Jungle amplified dub’s influence with thunderous bass, echo-laden textures, and rapid breakbeats. Toasting evolved into jungle MCing, while dubplates and exclusives kept the scene vibrant. By the late ’90s, garage dominated, but dub’s minimalist ethos inspired Croydon producers like Horsepower Productions to strip garage down, birthing dubstep.

In the 2000s, dubstep took shape in London and Bristol. Artists like Kode9 (Hyperdub) and Pinch (Tectonic) reimagined dub’s skeletal power with futuristic flair. Though mainstream dubstep veered into “bro-step,” the underground scene preserved its experimental roots.

Bristol’s DJ Stryda (Dubkasm) bridged generations with his Teachings in Dub nights, pairing traditional sound systems like Channel One with cutting-edge dubstep. Speaking in a recent feature for the Bristol Cable Stryda reminisces that when he teamed up with Pinch’s Subloaded night “You had people coming for dubstep, then they’d come downstairs and hear roots and dub sound systems for the first time,” Having such confluence between old dub and new dub inspired offshoors inspired a new wave of Bristol artists, including Bristol label owner Dan ‘Ossia’ Davies, who further fused dub’s spirit with experimental sound. Labels like Bokeh Versions and 12th Isle continue this leftfield evolution to this day.

Today, UK dub thrives. Veterans like Sherwood and Bovell remain active, sound systems still shake dancefloors, and dub’s legacy echoes through the UK’s ever-evolving musical underground. Whether or not it fits neatly under the term “dub” is a debate for scholars—but its influence is undeniable.

Further Reading

Local Authority: The Legacy of John Collins by Spice Route (2024)

Dub : Soundscapes and Shattered Songs in Reggae by Michael Veal (2007)

Further Listening

Further Viewing