Out of Nothing: OYC

A conversation with OYC in all that surrounds the wilfully obscure.

It’s a Spring day, but not the kind you’d expect. It’s London…a monochrome light matched with a bitter breeze. Thick cloud cover encapsulates the atmosphere, one suitable for the conversation that was due to take place with Andrew Hulme; once one quarter, now one half of O Yuki Conjugate. The band that pioneered a new sound whilst modestly ploughing a furrow amidst the changing trends of the industry…

Jake: Let’s start with the latest album ‘A Tension of Opposites Vol 1 & 2’. It’s not your typical OYC project and almost seems to be two projects in one, the A side filled with shorter, snappier tracks and the B side with more traditional OYC stuff.

Andrew: We were on our way back from our first gigs in Europe a couple of years ago, quite thrilled about playing live again. Rog had said he wanted to create shorts tracks, I wanted to stick with longer pieces. Three years later, we find ourselves in lockdown, doing exactly that, unable to mix and create the tracks as we normally did. We both worked in isolation away from each other, did what we wanted without the other person saying, I don’t like that bit or, let’s change that. Admittedly, mine wasn’t purely solo. I had used some prior recordings of saxophone and flute, they’re all fairly heavily processed and I ended up playing around with them quite a bit; that’s it really. We then had a choice, do we combine these and work on them like a normal OYC track? Or do we just put it out as it is, and we just decided there and then just put it out like that on a cassette; we didn’t have to worry about mastering, we could just do it ourselves really quickly. We’re pretty grateful for these times as we realise we don’t have to have one way of creating, there are other ways of doing it.

J: You’ve described there that your way of working has changed during this album but have your studio habits changed over your career at all? Your output has an extremely consistent sound considering what changes the world has gone through relative to music…

A: Yeah of course, we’re in our fourth incarnation of the band. Each time the working method is different. Currently this is mark 4 for us with the two original members, myself and Roger. We’re a bit like a married couple, in that we slag one another off to our faces… we don’t take much seriously. But as I said before we have these tried and tested methods, but lockdown has forced us to try other things out, and that’s been out of necessity, in a way, which is a good thing. I think limitations are good in whatever you’re doing, you just look at anybody who’s given an unlimited budget to do something, they always fuck it up. Look at Stone Roses second album…you see it everywhere. The most creative stuff is usually done when you’ve got nothing, when you’re literally picking stuff up off the floor and making art or music from it. It’s great, it’s original, it’s simply what surrounds you.

J: Is that the “post-punk” mind-set coming through…

A: Oh God, absolutely. It was completely liberating. In the sense that I’m certainly not a musician, but I always wanted to be in the band when I was 16. I was desperately jealous of people who had bands. But I couldn’t play; the influence came from the mind-set… Just do it. Don’t care, don’t worry about it, just do it. However, it was more than that, what it really meant was, you have a right to do it. I believe that’s an important lesson about life…It doesn’t matter what it is, you have a right to do it. You might be crappy at it, but you still have that right. This combined with our listening habits (Jon Hassell etc.) really enthused and inspired us, we just wanted to have our own have a go at it. We had the sounds and the ideas to play around with in the studio to give us the kick-start into this new world we became a part of. There was no sampling in those days, we used to work with a thing called a DDL, a digital delay line that had a looping facility. It had a button that dropped the sample rate; suddenly you’re in a whole new sound world and that was the gateway for us. It was a wow moment. You were listening to a new sound you’ve never heard before, it was the newness of it all that really thrilled us. And still does.

J: Your soundscapes are a big part of your sound, extremely capable of setting the scene…cinematic pops to mind. Alongside music you’ve had a career directing and creating films, are you a storyteller at heart?

A: I remember when I was kind of 18 and I got a Super Eight camera. This was when pop videos were just starting really in early 80s. That idea of images and music together created this new dimension, it was pretty amazing. And so, I spent four years at college doing just that, starting to weave images and music together to tell stories. I then learned the trade as a film editor, eventually working on dramas, went to Hollywood; blah, blah, blah. One day I realised I wanted to make my own films…30 years later after leaving college and I’m back in that place that I originally wanted to be in but with a whole raft of experience of narrative…how to tell a story; with text, with words, with music, with sound, with character. I think without that I probably wouldn’t have made films.

J: Do those skills transfer into your process in the studio?

A: I don’t know. When I personally make music, like with Volume Two of Tension of Opposites, I either have a story in my mind or I’m using the sounds to kind of move through a variety of different emotions. There’s a very loose narrative in there, you can feel the story but may not know the context. In the 70s there was this horrible thing called the concept album which we really kicked against. That was the height of decadent Prog Rock…The triple vinyl concept album that had these awful lyrics, by guys with long hair and high button waist bands. Naturally we really reacted badly to that kind of thing and so I have this fear of creating one. If there is a narrative, I bury it very deep, I won’t ever tell you, you may get a feeling though.

‘I dread to use the word masterpieces, because they’re really not; I think they’re just of their time.’

J: Music tends to be an expression of present emotion(s). Are you surprised that your earlier music is being dug up and creating a resonance with a younger audience?

A: Oh, it’s gob smacking to be honest. We just did those albums and nobody really listened to them at the time. Purely because we were just interested in it, and the fact that 30 years later or whatever, people are digging them up and thinking that they are…I dread to use the word masterpieces, because they’re really not; I think they’re just of their time. They’re unusual…artefacts of the time? I think what’s happened in the last 30 years is that there’s been a lot of crate diggers who have discovered these bedroom producers from the 80s, who were doing their own thing. And it’s kind of wonderful to be honest, at least we’ve had some recognition.

J: Did you ever come despondent by the fact that never caught on at the time?

A: Nah, strangely enough the stuff in the 80s all sold out really quickly. The first album was 500, the second album was 1000. Our third album was CD only and that did really well actually, I mean, we sold so many copies of it, but not in Britain. We took on this whole Editions EG ambient sound that people just hated at the time. It was seen to be an intellectual idea, people could not understand why you were listening to it, they couldn’t grasp the fundamentals of it.

J: I wanted to ask about your reincarnations. How has it worked with new members joining and bringing an alternate mind-set?

A: We just know what we like…somebody said to us that we’ve been incredibly consistent over nearly 40 years, and actually we’ve done pretty much the same thing…and got exactly nowhere. We’ve made literally hundreds of pounds out of it. Our sound is our sound, that’s it. It’s harder to get away from it now. That’s what we tried to do with Ocean Youth Club really, just do something that’s just a bit different, make it more electronic, less sort of organic and all the usual themes. I think as a musician, or non-musician, you tend to fall into what you know, and what you’d like to do and what you like your sound to be and it can be kind of hard to reinvent yourselves sometimes.

J: Tell us about working with Colin Potter?

A: We met him years ago, up north, when he had a studio in York. He then moved only a couple miles from where I live. I found this out, got in contact and we’ve been kind of working with him on and off over the last couple of years. He’s reworked the Sleepwalker album for us too. It was a live album, we tried it as a studio album but weren’t too keen. We preferred the live recordings. Once that was released we questioned what we’d do with all studio recordings. We gave them all to Colin and he has reinvented them into what will become the next release. I really like it, it’s another diversion for us.

J: How about the Symmetrix diversion?

A: Symmetrix…oh god don’t go down that route

J: It just caught my attention as it was so far gone from your normal ambient excursions…Was that your response to acid house?

A: Yeah, well, that was really Roger. He was quite influenced by ecstasy culture in the dance scene, whereas I was kind of a lot more suspicious of it…I still am actually, I think music has to exist outside of the drug realm, it has to connect to people outside of those environments. At the time, it felt like such a fad; everybody had to have a beat to their music, and we’d never put beats on tracks like that before, we started with electronic rhythms. But we moved away from all of that and suddenly, everything was you know…bm chh bm chh. I hated it really.

J: Have you naturally steered away from the commercial side?

A: It just seems wrong to try and make music for a market. For me, you’ve just got to go create your music. And the people and market will follow you…it will be found eventually.

J: Does this explain the time between albums?

A: I mean, the simple fact is, we never thought we could make a living out of it. Therefore, it was always in a way a serious hobby in that respect. We all had jobs, so making an album was quite a big thing. We would get together on a Saturday afternoon, do whatever we’d do, (this is when we had all moved to London from the North) and an album eventually emerged out of it. Virgin offered us to put out album out on a subsidiary that Paul Schütze was on. We were shocked, it was like wow, we get to put an album out on Virgin…

What happened? We said no. Because we couldn’t deliver to a deadline, they asked for it by the end of the year? Write an album in 6 months? You kidding? We were very, very slow. Nowadays, we could probably do it because me and Roger are very efficient at making music now, ironically. But at the time, it was like, Oh, God, we can’t turn the ocean liner around in six months. So, we turned virgin down. Sorry, love…you’re just not our type.

J: I wanted to talk a bit more about your sound. Tribal Drums & Rhythms feature a lot within your output. Is there a cultural fascination there?

A: That was more to do with the instruments that we had. For the second album, tongue drums ended up playing a large part within the sound, simply as we just happened to buy some prior to recording. We had been really interested in the organic sounds that the Fourth world lot were showcasing. It was a vibe that nobody had really heard before, let alone be interested in…Byrne and Eno “My Life in The Bush of Ghosts” was quite an influence, or My Life in The Gush of Boasts” as it’s sometimes called…

Our music has always been music of the imagination; it was always intended to take you off to other worlds and promptly leave you there…We were never interested in making statements with music, we were interested in just creating worlds and creating soundscapes and landscapes in the mind because it was what we were mostly interested in. It’s head music I guess in a lot of way or new weird stoner music as somebody described it the other day.

J: With that in mind, your rhythms and soundscapes have leaned towards the hypnotic spectrum. Are you spiritual in any way?

A: Anything but really…

J: Well occultism seemed a pretty popular source of inspiration for artists within similar circles. Did this ever find its way into your music?

A: I don’t think that was anything that we were ever interested in. We were kind of aware that other worlds were being created but that was all part of the imagination. All that stuff about Crowley and everything that surrounded it is fine as a theory, but it’s just bollocks basically. And I think nobody dares say that. They like the kind of language that’s a kind of pretence.

J: You released on Gordon Hope’s label, A mission, where Bible references were used as catalogue numbers. Were artists turning to other influences other than politics that punk seemed to have a grasp of at the time…

A: It’s an interesting thought. I think in some respects, it was it was more to do with that whole TG (Throbbing Gristle) world, they had a big influence on people’s interest in things like Crowley, rituals and music. Psychic TV were around and everybody had to talk about magic with a K, of with a V. And we just thought as a bit of a joke, to be honest. I come from a religious background. So, for me, anybody that’s trying to pretend to be religious and control people through religion sorry I’m not going there I’ve seen it and done it and lived it so why would I do it ever again, whereas lots of people got kind of sucked up into it. I think it’s more of an affectation than anything because in the end Psychic TV proved to be nothing solid whatsoever. It was all just Genesis’ fantasy in a way and they wouldn’t let the thing continue once they’d left. It was all about control and I think that’s what religion is ultimately, it’s like any power base…it’s all about control.

‘We’ve always wanted to make beautiful music, but realised the world is not really like that.’

J: We’ve brushed upon emotion but I wanted to ask about the mood of a lot of your music. Words such as doom-laden, dystopic, ghostly have all been used to describe you guys…melancholic also springs to mind. Do you find comfort in these emotions?

A: There’s more depth to it for sure, I can pin down where that comes from, the album “Return of the Durutti Column”. First heard when I was about 16 and was completely blown away by it. At that point, I’d only ever listened to heavy rock and punk when suddenly there were these delightful little instrumentals that were sort of mournful. To me they were about lost childhood, it was all about growing up. These plaintive little tunes that just evoke so much, it took me back to being a child for me anyway. I think if we took anything from the Durutti Column is probably that sense in that spirit I think that there’s something slightly mournful about that transition to becoming an adult, you don’t want to leave your childhood. It’s kind of beautiful…

J: Reassuring in a way, the dark is made to feel warm.

A: Yeah, the word beauty is quite interesting, because we’ve always wanted to make beautiful music, but realised the world is not really like that you know? Sometimes music just tends to become dirge…it gets dragged through the mud sometimes. Whilst your head’s up in the clouds, your feet are actually in the mud; it’s kind of good to have both aspects. So that idea that everything is pretty and beautiful. It’s not an accurate view of the world, really.

J: I know through watching your films you take everyday viewpoints/scenes and warp/morph them into something unrecognisable. Does this process translate, applying the same treatment and creating elements to tracks?

A: Oh, yeah. That’s what I’m interested in personally, discovering new sounds within the machine if you like. Taking recognisable sounds, turning them into something unrecognisable and that is a total delight to me. Any spare moments I have is I’m doing that.

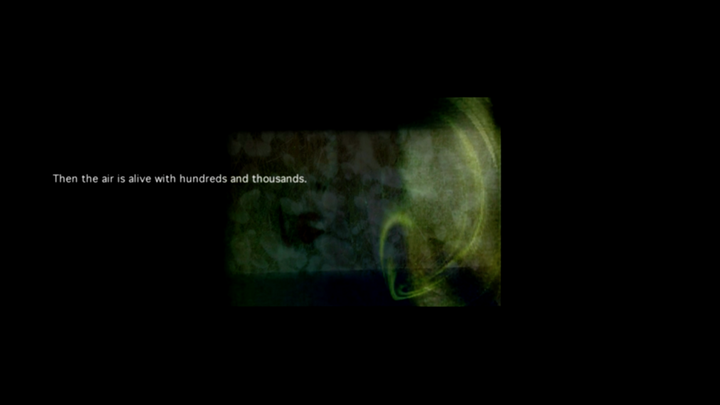

J: And the same goes for Sleepwalker?

A: Yeah, I do the same with imagery, creating abstract imagery. The same process applies with images and sound. I try and find new forms, shapes and colours within that which is then combined as a whole. Sleepwalker was an experiment, we added a narrative which is something we’d never done before. We worked in this way where the music was developing at the same rate as the images and the same rate as the dream like narrative. Somehow when all three of them combined in the live show, it just works. I can’t rationalise it more than that really. It shouldn’t work, because the narrative to most people won’t make much sense because it’s taken from dreams…why would anyone else’s dreams be of any interest?

J: Personal dreams?

A: For me yeah. I’ve spent years writing down my dreams and I look back at some of them and think this is complete and utter nonsense. And other ones seem to have a resonance beyond, they’ve transcended time and I’ve tapped into some of those ones. There’s certain images, like being in a waiting room, that everybody can understand amongst other scenarios. I think most people’s dreams are very banal and only relate to them personally. I tried to make it a little bit wider than that. Sleepwalker just came about from a circumstance of us playing live, we were forced into making a film to go with the live thing.

J: In a previous interview, you said you attempted to re-kindle a feeling for live events which you then gave up on…do you not enjoy performing live?

A: Up until three years ago, no, absolutely hated it. And then suddenly we found ourselves a way of working together that we could do, strangely. Maybe we matured or maybe we found ways of playing that we never found before; maybe we found technology that had gotten better I don’t know. Probably a combination of all of that. So now both of us really enjoy playing live. We get a real buzz off it, it’s nearly better than real life. Cosey also taught me a lesson… ‘keep it simple’. That went a long way to shaping the way we played.

J: Seeing as you’ve described yourselves as a budget Eno, I wanted to ask you a question that was asked to him. In the notes of Reflection, he wrote of ambient music ‘I don’t think I understand what the term stands for anymore; it seems to have swollen to accommodate some quite unexpected bedfellows.” What surprises you about the way that ambient music has evolved?

A: I don’t believe it’s what it originally meant. For us it was always about a quiet introspective music, something that you could put on in the background, you either listened or you didn’t. It was a style of listening more than about the music itself. Through chill out music and its popularity in the early 90’s within rave culture, ambient has just come to mean ‘instrumental’.

I’ll tell you one thing though that I’m happy with… the audiences. They are way more open minded than they’ve ever been. I think that’s had a lot to do with ambient music. Minds are very open to listen to anything nowadays, which I think is fantastic. It was all very divided and tribal when we were young, partly because it gave people an identity, and now the idea of identity seems to have disappeared. Partly to do with the internet. What you’ve got is this open mindedness, you could literally just have someone honking on a saxophone and people will be nodding along to it. If you just look at the front page of record stores, it’s incredible what you find.

If you’re convicted enough in what you’re doing people will listen to what you’ve got to say. If you have a brand or whatever you want to do, the way you present it to the world is absolutely of the most importance. Because that is what people see and that is how people will access it first. It could be a scrappy hand written note or it could be seductive artwork, the choice is yours. It gives you the opportunity to raise yourself out of your upbringing and do something original or unusual, you control all the elements, you just need the idea. For me it comes back to the question of identity; who you are, who you want to be and how you want to be seen to be. Music has always had this ability. When rock n’ roll came over in the 50’s…it was a way of getting laid basically and earning a living. The greatest thing about it…anybody can do it.

J: What’s kept you guys going for this long? I think it’s special that you’ve managed to keep making music this long, I wouldn’t say it’s a common circumstance with a lot of artists.

A: We like to say that we were too lazy to split up. Which is true to an extent. The truth is we never started it by wanting to make a living out of it, we did it for the love of the music. That love has still remained and there’s been no commercial pressure to cause problems. Every time there was a natural break coming we’d just take several years off and then eventually find the love again and reform in a different shape. You’ve said the music is remarkably consistent over nearly 40 years. Well it’s quite simply because we’ve only ever had one idea and we just keep doing it. Maybe we’re the Status Quo of ambient?