In Conversation With Maggi Payne

A conversation with US composer Maggi Payne, retracing her wild journey from Texas to Mills College’s CCM.

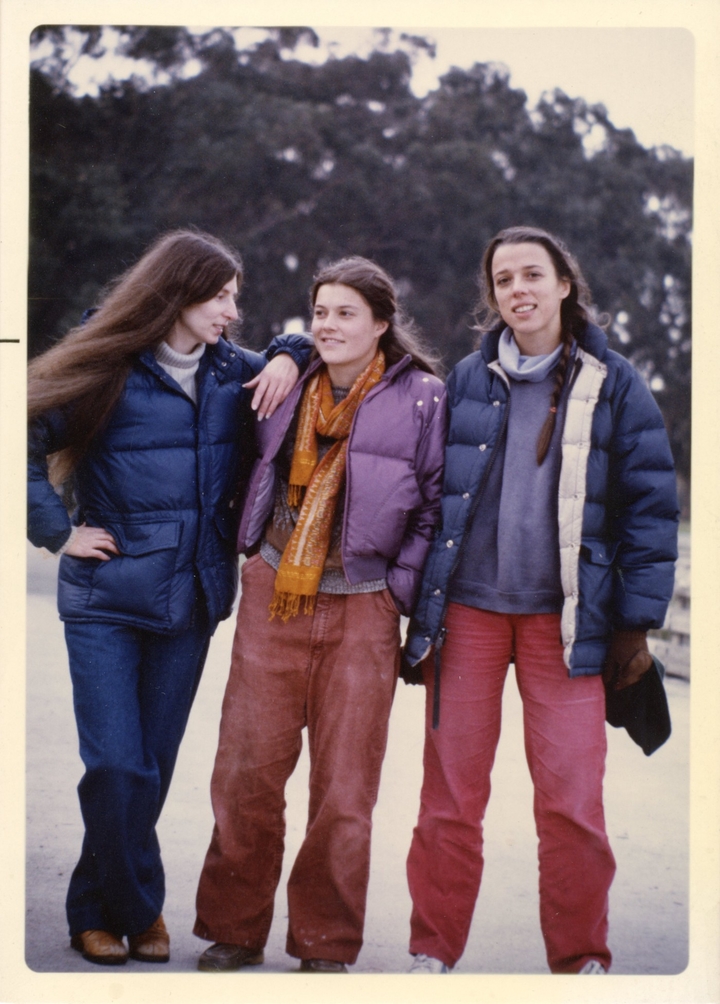

Following the announcement of Mills College’s forthcoming closure in 2023, Christine invited one of a-kind visionary composer and former co-director of the Center for Contemporary Music to share her fascinating journey. Part of MoMA’s 1979 Sound Art pioneer exhibition and a core member of Mills College’s experimentations since 1970, Maggi Payne discusses her trailblazing multidisciplinary work.

Christine: Hi Maggi, how are you? Hmm, it seems that I have an issue with my camera, can you see me?

Maggi: Hi there. I’m okay, yes, I love it. (laughs) I find it fun. You’ve enabled your video?

C: I’m good, thanks. Yes.

M: It just popped up. (laughs) So can you tell me a little bit about yourself? I looked you up on the web.

C: Well, where can I start. I have a degree in Performance Making from Goldsmiths University. I feel Mills College, where you co-ran the Center for Contemporary Music for 26 years (from 1992 to 2018), embraces Noods Radio’s experimental and communitarian spirit.

M: I love radio, I always have. I have maybe five shortwave radios. I worked in radio for 11 years as a production engineer. It was quite a job, and I really loved it. I was hired for three months to clean up all the noise and fix everything on the extensive playlist of songs and make them sound good. Little 45 RPMs, and some of them were on LPs. I was still working on this project after three months, and they just hired me, so that was really great. I was working four jobs simultaneously for two years and then I think it was just three part-time jobs for another nine years.I worked the late night shift and when I drove home, I would have to park my car in the right direction so I could remember which way to go to the next day’s job because it was back-to-back jobs.

C: Haha. When did your interests in electronic music and sound start?

M: In the 70s. I was really focused on electronic music. I’d played flute since I was nine. I’d always been excited about all the extraneous sounds that you can make with the instrument that weren’t necessarily just pitched sounds — whistle tones and blowing the air through the flute with the closed embouchure hole and fingering notes to change the airy pitch.. I just kept and kept working on it, specialising in extended techniques and contemporary music from the age of nine. When I went to the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign for my Masters in Performance, I was so excited, because they actually had a classical studio, with equipment that used large clipping dials to change the frequencies. There were some Moog modules and that was exactly what I was looking for to expand what I could do. I got so hooked on electronic music. That lasted quite a while and I think by the mid 80s, I was looking for other sound sources beyond the electronic world.

I was an inveterate recording engineer from the age of ten, when I got my first monster sized tape recorder that I could barely lift (laughs). I recorded from very early on, and then I started thinking that I should really start pulling all those resources together and start expanding once again into acoustic modifications of sound. Sometimes the sounds are so abstract in fact that you wouldn’t be able to identify them, in part because of the ways I was recording them. Other times I would process them beyond recognition, intentionally, to build other worlds of sound in the natural world.

C: So it was in the 80s that you developed your interest in microsound?

M: Yeah, but I have to say I flip back and forth a lot, I live in a lot of worlds (laughs). So I love electronic music and I’m still doing a lot of electronic pieces now. I love recording sounds and I’ve been doing that really extensively during these lockdowns that we’ve had because of Coronavirus. The noise level went way down and enabled us to hear things that would usually be very difficult to hear. Now that people are back in cars and the freeway is just roaring and the airplanes are flying out constantly, those sounds have gone away again. It’s very hard to hear them unless you’re there at two in the morning and even then, the trains are coming back and forth. In the meantime, I’ve dragged out my Aries modular system that I had built from a kit around 1977. I started working on my Aries again because I had to make sounds somehow set apart. When I’m recording sound with mics it’s so critical for me to have the ideal mic placement. I often use these little tiny stepper motors that are about as big as the tip of my finger. This tiny thing that you can barely hear, when I build it into a piece, becomes this monstrously huge

thing because you’re inside of it. It’s fun to be a little playful with things and to warp sizes and make other worlds that don’t really exist.

C: Yeah, that’s why I love your album Arctic Winds so much.

M: Excellent. I love the design. It’s beautiful.

C: I watched your track Apparent Horizon on Vimeo, I just love it. Can you share anything about its backstory?

M: As with many of my works, it’s got an underlayer. So many of them are about ecological issues. That work in particular has a lot of images that I shot in desert environments, and I consider those places to be where we really don’t belong, we should leave them alone, leaving no footprints. I was trying to express how beautiful so many of these places are and to hope that the human stamp doesn’t occupy them. We don’t need to go everywhere and build everywhere, we can just visit and appreciate them for their beauty and leave them alone, and it is extraordinary to be in those places. Often I find places where there have not been many people or any sign of other people around so it’s a little scary; sometimes if my car breaks down… (laughs).

“Those extremes tend to find their way into my music. That’s why you find these huge events separated by very delicate areas of sound, not knowing what’s going to come next, then you’re thrown into another world. So you’re just sort of on this journey with me, and I try to get you inside that sound.”

C: Your album Arctic Winds also seems inspired by science fiction, but maybe I’m wrong?

M: I love science fiction, of course. I think it’s that I have this very deep connection to desert environments. I was born in Texas, raised in the Texas Panhandle. There’s some farming in the south side but we lived right where it became desert and it was unbelievably quiet. There’s a certain beauty to the desert that many don’t see, but to maintain your sanity you need to really appreciate the vast expanse, and that you can see forever. Nothing is in your way. So you have that sort of long view, but you also have this fascination with every little crack in the earth where the soil is very dry, and breaks open, and every little detail becomes huge. And I have memories of sitting on the back steps with our view not obstructed by anything, where we would watch as the amazing thunderstorms rolled in, and try to guess whether those funnels that were forming, are really going to land and hit as tornadoes. We were thankful that they all folded back up into the clouds. But the lightning storms were spectacular. And the thunder, you felt it in your chest and it would just roll forever and the hail storms, the hail is huge. People would have to have the tops of their cars and their roofs replaced because it hammered so hard. And when it snowed, it would create what we used to call submarines because the winds were always so strong. The Texas Panhandle was one of the windiest inhabited places in the US. There would be big mounds of snow that would collect over the fence. You’d have anomalous bare sections, and then there would be ten feet of snow. I mean, the extremes became part of your make up as a human being.

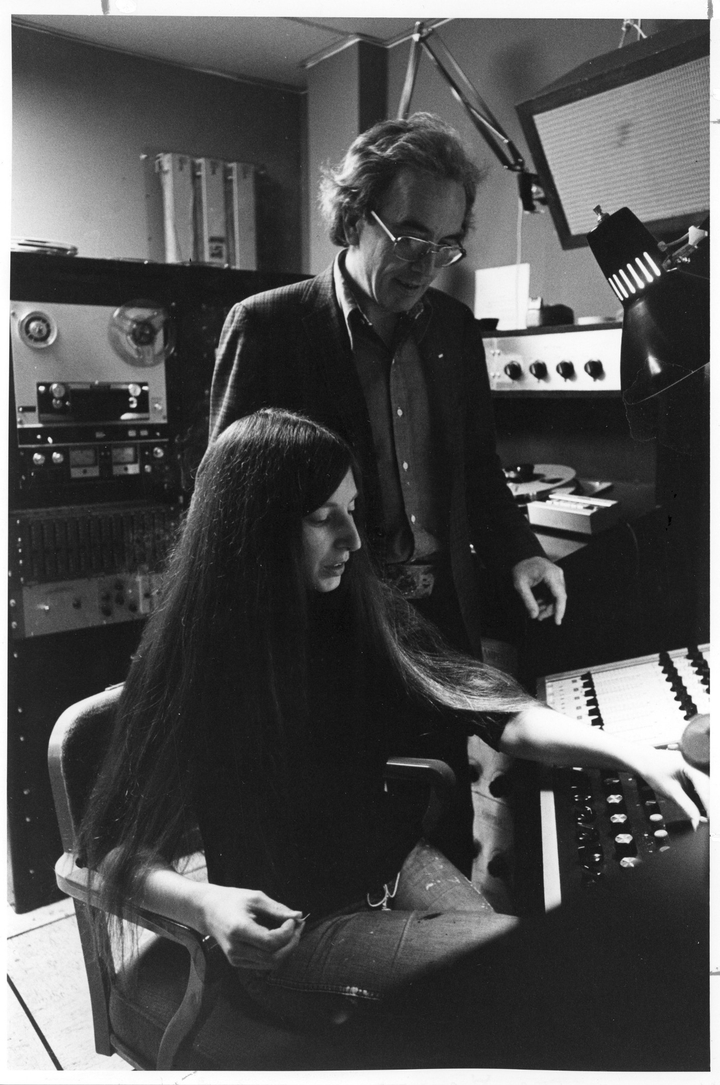

Ralph Payne.

So these huge events would come in, and rain so hard that you could hardly catch a breath — you’d have to protect yourself to not drown if you opened your mouth. And the incredible and very terrifying dust storms that were so strong that at elementary school, trying to walk home against it, you got sandblasted. And the sky turning very dark brown and the sun being quite dark orange and barely visible. Those extremes tend to find their way into my music. That’s why you find these huge events separated by very delicate areas of sound. You don’t know what’s going to come next, then you’re thrown into another world. So you’re on this journey with me, and I try to get you inside that sound, as if it’s almost coming for you, or at you, or from within you. And you’re in this space, an imaginary space, and I hope the listeners are creating their own visuals for the space that they’re inhabiting within that sound, so that they can navigate and have their own scenarios.

C: You made some major multidisciplinary collaborations with video, electronic/computer artist Ed Tannenbaum in the 1980s. Can you recall how you met and share how it was to work with him?

M: Ed Tannenbaum and I met in 1979, when he became the Technical Director of The Center for Contemporary Music at Mills College. He left in 1980 for a residency at The Exploratorium, a museum of science, technology, and the arts. Nick Bertoni and I were Artists-In Residence there from 1983–1985, where we worked with occasional very valuable help from the staff to build a flame speaker. I had seen/heard one at a science fair at Northwestern University and persuaded Nick to help make one. I located one at United Technologies and, after getting security clearances, a very kind scientist excitedly demonstrated it for us.

At the Exploratorium we were able to get one up and running in a couple of days using oxy-acetylene fuel, but Frank Oppenheimer, founder and director of the Exploratorium, wanted us to use natural gas, which unfortunately burns at a much cooler temperature but was provided for free. It took two years and many experiments to make this interactive exhibit happen. We placed two electrodes carrying audio from a microphone, a small electronic keyboard, a cassette machine playing popular songs that mentioned “fire” (think Johnny Cash singing “Ring of Fire”), and a high voltage direct current in a 10-inch-high gas flame seeded with chemicals, resulting in high fidelity audio produced by the flame. We built an elaborate kid-proof structure with sensors that shut down the entire system if a pressure of 10 pounds or more was detected on any of the “leaves” surrounding the marble table that held the electrodes.

Eddie and I stayed in touch and when he showed me the capabilities of the video system he created, I asked if I could bring sparklers, other light emitting objects, and his retroreflective tape to his studio so he could process my movements using a digital frame storage video system he designed and built, and a Fairlight video processor. The video was created in real time. I subsequently intercut several takes to provide the final version of my work, Circular Motions. He had developed the system for a wildly popular interactive installation at The Exploratorium. Eddie has installations in science and art museums throughout the world, but also loves to perform live. From 1981 on he asked me to compose music for several works.

At times he would have already determined a tempo with the dancer, so I carefully matched the tempo (Viscous Meanderings/Flights of Fancy). For Queue the Lizards/Ahh-Ahh he mentioned waves and a body melding with the waves so at first, it was difficult to distinguish the undulating human body from the motion of the waves, then she slowly emerged. He was thinking about using mechanical toys for the middle section, but that went by the wayside for the visuals, although that idea drove the audio. He envisioned snakes and whips as gestural ideas for the final section. For Awareness/Gamelan, I’ve always loved the sounds of gamelans and had just purchased a Yamaha DX7, which, with a few programming alterations, was the perfect synthesizer. Eddie heard gamelan music around that time and really liked it, so we were definitely on the same page.

C: Your dear friend Annea Lockwood burned a piano in ’68 to record fire. Is that something you were aware of?

M: Oh, yeah, absolutely. Piano burning? Yeah. She did a series of them. The minute I heard about that I said, I’m in love with this person. She always makes a point of saying that these were pianos beyond repair. They were no longer useful. She also recorded a piano placed in a pond. It was really funny. It was a pond maybe ten miles away from where I grew up in Texas. I didn’t know about it until much later. And then I think she did one in her backyard garden, and elsewhere.

C: Have you had similar experiences?

M: Yes, well, I’ll record anything that sounds interesting to me. I did build a Jacob’s ladder, that was really fun. I found a neon transformer and hooked it all up. There are these electroluminescent wires, called neon wires. It’s extremely dangerous, of course, but I didn’t realise. Besides the high voltage and all that, I was recording it in a relatively small space. I realised that I was getting kind of dizzy. I couldn’t breathe very well. I did a little more research and it’s very dangerous, there’s ozone, it produces a lot of ozone, that’s not good for you to breathe (laughs). I shouldn’t have been doing that, I was just trying to have a really quiet environment. I made a piece called System Test using the Jacob’s Ladder. It exclusively uses the sounds derived from those recordings. I dance to go with it using electroluminescent wire, called neon wires wrapped around four dancers, including myself, and performed that piece several times with different dancers.

““It was so much about how the electronics responded to what we were doing. So we were exploring how to try to edge into the correct pitch to see just where the computer would catch it and respond, lower than the frequency that it should be. We’d then just flood it with pitches to see when the computer would react.”

C: You did a lot of collaborating during your time at Mills. How was it to collaborate with David Behrman?

M: Oh, yeah, On the Other Ocean (1978), with David Behrman was one of my favourite experiences. It included the responses of the computer to the notes we played. Certain notes would cause certain actions. David is brilliant at this, allowing us to have some real control over the shape of things. It was so much about how the electronics responded to what we were doing. So we were exploring how to try to edge into the correct pitch to see just where the computer would catch it and respond, lower than the frequency that it should be. We’d then just flood it with pitches to see when the computer would react. “Blue” Gene Tyranny was the recording engineer. We just did single takes of segments one, two, and three. In take four there was a technical issue. So we did that one twice.

C: “Blue” Gene Tyranny reviewed The Extended Flute on allmusic, rating it 10/10!

M: That’s great. I love him so much. He’s just the dearest person. We’re both from Texas. Really, unbelievably incredible pianist. Just wow. I’ve been digitising a lot of tapes from the CCM archive and I was digitising tapes of the performance of Perfect Lives by Bob (Ashley) and “Blue” (Gene Tyranny). It was in 1981. Those performances were in every style possible and had such finesse and intelligence. He’d learned this Russian technique of performance when he was quite young, and he had a feather touch. You feel like he’s barely playing. I don’t know how to describe it. They did all the segments in one day, starting at 11am. I think the last performance was 11 at night. So for an entire day, that intensity, with that much technology and that much stamina. It was quite amazing.

“It was an extraordinary feeling to come to Mills, where people aren’t challenging one another all the time. They’re challenging themselves and helping one another. It’s all about community. If you forget to turn in the mic that you borrowed, you’ve harmed the community. Right? That’s not acceptable. It’s so wonderful to see lifelong relationships happen because of the experience there. The students become part of this fascinating history and camaraderie”

C: Mills College fosters a strong sense of community, which is important for Noods too. Having been such a core member of Mills, from student to teacher, do you have any advice for us to sustain Mills’ ethos?

M: From the very beginning we encouraged students to work across disciplines, to collaborate both within and beyond music, to experiment, to continue to push the boundaries. If you’re a competitive person, that’s okay, as long as you feel that you’re just competing with yourself, which is something I think most of us do. You always want your next work to be even better than the one that you just did. I was raised in an extremely competitive environment from age nine, auditioning for city orchestras at age nine and ten! It was an extraordinary feeling to come to Mills, where people aren’t challenging one another all the time. They’re challenging themselves and helping one another. It’s all about community. If you forget to turn in the mic that you borrowed, you’ve harmed the community. Right? That’s not acceptable.

It’s so wonderful to see lifelong relationships happen because of the experience there. The students become part of this fascinating history and camaraderie. I also should say that we’re not insular, we encourage people from all disciplines to take our classes. They have so much to contribute, a different perspective that enlivens what they create, with people from physics, art and literature and dance, everything. In some classes, I had more non-music people than people in music. Yes, bring it on! People from all around the world. Several students from China and Japan said that they were taking courses in electronic music, and in recording engineering, because they were not available to them in their homelands. They were heading off to be doctors or whatever, which was fantastic, but they wanted to express themselves in a different modality, and be very creative in the arts, and they were always just amazing. For dancers, it’s in the body with a wonderfully visceral and spatial approach to sound. People have set my work to dance, like Deborah Hay and many others. It always fascinates me. This deep connection with the body and sound. To have this dialogue across disciplines and you learn from it, but it also surprises you, I guess.

C: Thanks so much, it’s important to keep this in mind. It was really nice to talk with you.

M: Many thanks to you. It was such a pleasure to talk with you. Bye bye.

Reissues of Maggi Payne’s Ahh-Ahh and Arctic Winds are available on the Aguirre Records Bandcamp page.